Is the US’s multi-billion-dollar LIHTC the worst housing program in the world?

COVID-19 pandemic housing crisis continues

Short on time? Read to the red line for the highlights. Want to learn more? Items that are bolded in the top section are expanded upon beneath the red line.

Links to our projects: Everything you need to know about reforming the American housing system in 4 episodes | Podcast | YouTube channel | previous issues of this newsletter | recommended reading | homepage

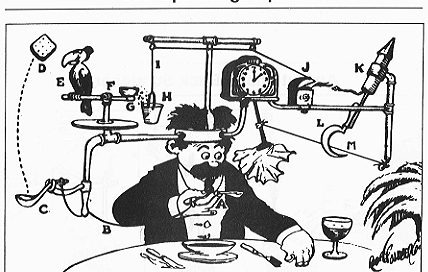

The $10.9 billion Low Income Tax Credits (LIHTC) program is so needlessly complex that Rube Goldberg would blush. That’s probably the best way to describe LIHTC: if Rube Goldberg and the Monopoly Guy were to design an affordable housing program, they could not design a program as needlessly complex nor as friendly to real estate tycoons as LIHTC.

The practical way to finance housing construction is to offer cash or loans to build homes. LIHTC does not offer cash or loans, but several years’ worth of tax credits. Of course, you can’t pay an electrician in tax credits, so developers are expected to find investors who can give them a stack of cash to build an apartment building in exchange for those tax credits. Typically, the tax credits change hands multiple times, with each middleman taking a cut. This is because LIHTC deals are so complicated that experts in LIHTC (called “syndicators”) are needed to match developers to investors.

This isn’t a poorly-thought-out program with unintended consequences of developers needing to go hunting for partners; this is the way the program was designed to work. This extraordinary complexity leads to buildings that cost tens of thousands of dollars more per unit to build.

The Monopoly Guy would design a housing program that allows the rich to get richer at the expense of the public, and LIHTC is extremely effective for this goal. LIHTC developers need not be nonprofits, and the feds only require the housing they build to be affordable for just fifteen years (though states can double this to 30 years). After those fifteen years, a for-profit developer can gleefully raise everyone’s rent several-fold, to the highest level the market will bear. Aside from for-profit developers getting subsidy to build (deferred) for-profit housing, all the investors who profit in the short term from the tax credits are already-rich investors or banks.

Finally, the program is so complex that it cannot be audited. This means that if developers or investors help themselves to more money than they’re supposed to get, nobody will ever find out. Three people in Florida went to prison for pocketing $34 million of LIHTC money; they would have gotten away with their crime except two employees uncovered their deceit and turned them in. Without the honesty of the whistleblowers, the three never would have been caught: the program is so complex that there is no other way to know about millions of dollars being stolen. The prosecutor on the case remarked to reporters that LIHTC “has been described as a subterranean ATM, and only the developers know the PIN.” The IRS awards the tax credits but does not even verify if projects were completed on time or on budget, and an auditor testified to Congress that the "IRS and no one else in the federal government really has an idea of what's going on" with the LIHTC program.

Because of the program’s many benefits to the wealthy – and the general public’s inability to understand what is going on – the US continues to spend $10.9 billion per year on the program. That money that could be better spent building more housing, benefitting more people, and keeping important decisions under democratic control. For examples of how to do this type of program right, check out episodes 1 and 2 of our Housing for All podcast on Singapore, the Netherlands, Austria, and Sweden.

Even the acronym (it’s pronounced “Lie Tech”) is lame. The program is so absurd that a savvy consumer of news media will conclude that a program this stupid can’t exist and Housing for All must be fake news. Regrettably, LIHTC is not fake news; rather, at $10.9 billion per year, LIHTC is the largest affordable housing construction program in the United States. LIHTC has built or renovated approximately 2.3 million units of housing between its inception in 1987 and 2017. There are only 20.2 million units of multifamily rental housing in the US, meaning LIHTC has thus subsidized more than one out of every 8 units.

Housing policy updates

We’re still catching up on housing policy news that happened while one of our authors was on parental leave.

In November, Minneapolis-St. Paul voters approved a rent stabilization referendum. Once the measure takes effect this May, rents cannot be increased more than 3% in a year. Real estate and other opponents of the referendum spent a whopping $4 million dollars trying to defeat it – or 7 times what proponents spent. That money was spent hawking lies about rent control, falsely claiming that housing policy experts are unanimous that rent controls lead to disastrous deferred maintenance and a collapse in construction. People increasingly do not fall for these lies anymore.

We took an in-depth look at the extensive use of rent controls outside of the US in the second episode of the Housing for All podcast. Many countries internationally have been using rent controls for decades. In fact, all five of the countries we looked at in the series relied on rent controls to reform their housing systems.

Tampa Bay finally ends a shockingly bad program:

The department came under fire from the Hillsborough County branch of the NAACP and other civil rights groups after a Tampa Bay Times investigation in September revealed that officers sent hundreds of letters that encouraged landlords to evict tenants based on arrests, including some in which charges were later dropped.

The investigation also showed that officers reported tenants after arrests for misdemeanor crimes, the arrest of juveniles and arrests that happened away from the landlords’ properties. Roughly 90 percent of people reported were Black tenants, records show.

New Orleans passed a right to counsel for tenants in eviction court for 2022.

When researchers sent out fake rental applications using names that sounded Black, white, or Hispanic (err, “elicited a cognitive association” with a “particular ethnic group”), they found an astonishing level of housing discrimination across the US.

Pandemic not over

Throughout the US, emergency rental assistance programs – which are supposed to cover unpayable back rents for renters who experienced financial hardship during the pandemic – are still distributing money. California’s program will apparently fall billions of dollars short, with a similar shortfall expected in New York. Meanwhile, Florida landlords hoping to cash in on the hot housing market are openly flouting the minimal requirements of rental relief programs after accepting thousands of dollars in federal aid. Ongoing struggles over the emergency rental assistance program in Baltimore are particularly dire.

In Houston, January evictions were up 13% from the historical average for that month, indicating a clear failure of emergency assistance programs there.

Renters in Florida continue to get evicted due to hardships from the pandemic; a representative of the agency that covers parts of Florida gave a sense of the mammoth scale of distributing emergency rental assistance:

[T]here are more than 700 people employed through the Our Florida program to support families interested in assistance. The program receives more than 11,000 calls to its support line each day. [In December 2021], the program received more than 300,000 calls.

Now, back to LIHTC

A wild goose chase for funding

As mentioned at the top, a sensible way to fund a housing construction program would be to simply give money or loans to build housing. In addition to the complexity of using tax credits rather than cash or loans, LIHTC projects are even more complex because the LIHTC tax credits by law can only cover a portion of the cost to build an apartment. That means that developers have to look for multiple sources of funding in order for the project to proceed. A study of California LIHTC programs found that an astonishing 89% of LIHTC projects required at least four sources of funding, and 9% required more than eight. This needless administrative complexity adds tremendously to the cost:

On average, every additional source of funding on a project is associated with an increase of $6,400 per unit, or 2 percent, in total development costs…A project with eight rather than four sources of funding will cost on average $24,000 more per unit.

$24,000 extra per unit. What a wasteful program. Yet this estimate doesn’t even count indirect costs incurred by such staggeringly complex deals. For instance, developers have to own the underlying land before they can apply for LIHTC; when it takes over a year to secure a half dozen different funding streams, that’s an extra year of payments on the loan used to buy the land. Someone involved in financing LIHTC projects

noted that the need to routinely layer four or more sources of gap financing increases the development timeline. Not only does this delay the production of much-needed housing, but that added time to secure multiple funding sources results in “additional carrying costs associated with having an active development going. They might have a land acquisition loan, they might have pre-development loans that are outstanding. All those become the costs of the development, whether the developer is financing that cost internally or going out and getting third party sources.”

Another respondent reflected on a project they worked on in Washington, DC, “where it took over a year to close due to the complex financing structure. It had two Housing Authority soft loans, LIHTC equity...and [the] construction and permanent loan was a syndicated transaction between [two financial institutions]. With the various parties involved, closing of the loan construction was delayed by over a year from the original estimated completion date, driving up costs and lengthening the timeline.”

Again, none of this is actually necessary; social housing is successfully built in countries using far more straightforward financing (Singapore, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden).

All this complexity invites fraud

Because tax credits are transferred so many times, the arrangements are too complex for the IRS or the state agencies that award tax credits to meaningfully audit for fraud prevention. For example, in 2015, six people in Florida were convicted of stealing $34 million from eight different Florida LIHTC projects. The scheme was only revealed when two whistleblowers uncovered their supervisors’ lawbreaking and reported it to the FBI. The lead prosecutor on the case argued that the Florida agency tasked with awarding the credits had no way of detecting the fraud that was occurring, despite totaling tens of millions of dollars. Absent whistleblowers, the fraudsters would have gotten away with their crimes. The prosecutor strongly believed that even more fraud was occurring, telling reporters that LIHTC "has been described as a subterranean ATM, and only the developers know the PIN."

LIHTC lacks even the most basic oversight. For example, the IRS does not even verify if projects were completed on time or on budget. An auditor from the Government Accountability Office testified to Congress that the "IRS and no one else in the federal government really has an idea of what's going on" with the LIHTC program. Indeed, an investigation by NPR/Frontline reporters raised additional reason for suspicion. They found that in 2014, the LIHTC program had 66% higher costs than in 1997, yet 16% fewer units of LITCH housing were built in 2014. This trend could only be partly explained by higher construction costs and other factors.

A temporary fix to a forever problem

As mentioned above, LIHTC housing is reserved as affordable housing for 15 years (though states can extend this requirement to 30 years). This means that during the 15-year “compliance period,” only low-income households can move in, and each household must be charged exactly 30% of their total income for rent.

Because the program is relatively new, most LIHTC housing is still held to temporary affordability requirements. And, most LIHTC housing for which the temporary affordability requirements have expired still charge affordable rents. This is because most of the initial applicants for LIHTC were nonprofit organizations with a mission to provide affordable housing, even without a mandate to do so. However, for-profit applicants have since been awarded an increasing share of LIHTC credits, and a study commissioned by HUD predicted that much LIHTC housing will eventually convert to market-rate, unaffordable housing.

Imagine a very poor person who makes the federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour but only is given 20 hours per week so the employer isn’t required to provide health insurance. Their salary would be $7,540 per year, meaning their rent would be $7,540 x 30% = $4,524 or $377 per month. Market rent for a modest apartment might be $1000 per month; thus, when the 15-year compliance period expires, this person’s rent would nearly triple.

A current example in Los Angeles bears this out; when the compliance period for a LIHTC development named Hillside Villa expires later this year, some tenants are facing an increase in rent from $900 to $3,000 per month.

In sum, it makes no sense for the public to support – at great expense – the construction of affordable housing that is lost to the for-profit market in less than a generation. This is especially true as rents and housing prices continue to rise nationwide, and more and more Americans struggle with affording a place to live.

Mixing profit-chasing cutthroats with nonprofits…what could go wrong?

Obviously, the best-case scenario for LIHTC is a nonprofit developer being awarded the tax credits. As discussed above, once the 15-year compliance period has ended, the nonprofit will keep those units affordable due to its social mission.

But even this is not foolproof, owing to the terrible design of LIHTC. When a developer undertakes a LIHTC project, the investor who actually provides the cash is technically a co-owner of the building. The investor is supposed to allow the developer to buy out the investor’s share for well below market value. But one innovative investment group discovered that this requirement is actually on the honor system, and has been aggressively suing nonprofits to force them to sell the properties on the open market. Once listed on the open market, the property is gobbled up by a for-profit company that hikes rents as high as it can, and the investor walks away with a huge payday. This occurred in Seattle, where 20 buildings of senior housing were sold for a whopping $250 million, throwing thousands of poor seniors to the streets in the process. A nonprofit in Florida has spent a shocking $1.5 million in legal fees to stop this from happening, and another nonprofit in Pontiac, Michigan, and one in Brooklyn, NY, have ongoing, six-figure legal battles over senior and low-income housing, respectively.

Meanwhile, a Boston nonprofit estimates they will have to spend $500,000 defending 36 buildings from investors. That $500,000 had been set aside to build a new community center and pay for some much-needed repairs. Ironically, the nonprofit only used LIHTC to make building repairs in 2013; the housing project was started by the nonprofit nearly a half-century ago in the 1970s. In other words, a for-profit investor is seeking to destroy a pillar of the Boston community through the LIHTC program.

The amount of housing that can be built changes with tax policy

As you might imagine, such a complicated program has unintended consequences. Because the program works by forgiving rich peoples’ taxes, the amount of money that can be raised for affordable housing construction depends on how much rich people are being taxed. If – as happened in 2017 – corporate taxes are lowered, then tax credits are worth less to wealthy investors and they are willing to pay less to get them. That means that less cash for affordable housing and less housing that can actually be built. Per PNC Bank, the 2017 corporate tax cut resulted in a drop in value of LIHTC tax credits by 12-18% – a massive loss that actually led to some affordable housing construction projects being canceled.

The food is terrible and the portions are so small!

Finally, the size of the program is not congruent to the scale of need. When an astonishing quarter of all renters spend more than half their income on rent, it’s clear that the program falls well short of the need for affordable housing. Again, LIHTC costs $10.9 billion per year (with much of that lost to profits, administrative waste, and fraud). By contrast, the federal government devotes trillions of dollars to subsidizing homeownership, for-profit developers, and landlords, an issue we explored in depth in episodes 3 and 4 of the Housing for All podcast.

If the government is so generous in subsidizing well-off homeowners and rich developers, why is it so stingy with low-income renters?

The opposite of democracy

LIHTC seems to have been designed to prevent ordinary citizens from utilizing it, for two reasons. First, the high degree of complexity of the LIHTC system means that only specialists can understand the program well enough to apply. Remember, not even developers and investors are savvy enough to use the program, and normally have to hire a LIHTC expert to set up deals. By contrast, comparable programs in other countries require developers to solicit and incorporate input from future residents, with Austria being the best example. Second, because LIHTC legally cannot fund an entire project, only people with the ability to provide or solicit six- or seven-figure investments can actually apply for LIHTC.

A group of concerned neighbors in a low-income neighborhood in need of affordable housing opportunities would not have the ability to understand the LIHTC process, nor the capacity to raise several hundred thousand dollars in order to even apply. In other words, LIHTC benefits tend to go to the most savvy developers, and not necessarily to projects that address the greatest need.

The end result is that the public has no say over how the tax credits are used; housing may not be built where it is most needed, and basic decisions about urban planning are ceded to wealthy investors and technocrats. Since all this is made possible by the taxes everyone else pays, LIHTC is the opposite of democracy.

We are a nonprofit organization. All of our content is freely available and most (including this newsletter) is reusable under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our mission is to educate the public about the urgent need for reform of the American housing system and successful housing systems that point out how we can secure housing for all.

Please send in tips—you can do so in the comments or reach us through the web at housing4.us.

We’re interested in any reporting or resources on housing, even if they are several years old. Reporting does not need to have a national scope; local reporting is great!

We especially want to hear if you had a housing-related tragedy happen to you. In our housing system, tragedies happen every day and could happen to anyone. But unless more people understand this, nothing will change. Consider letting us share your story so what happened to you never has to happen again.

Images (public domain): Rube Goldberg’s cartoon “Self-Operating Napkin” and Rich Uncle Pennybags.